Personal Lessons From Taking Over SXSW

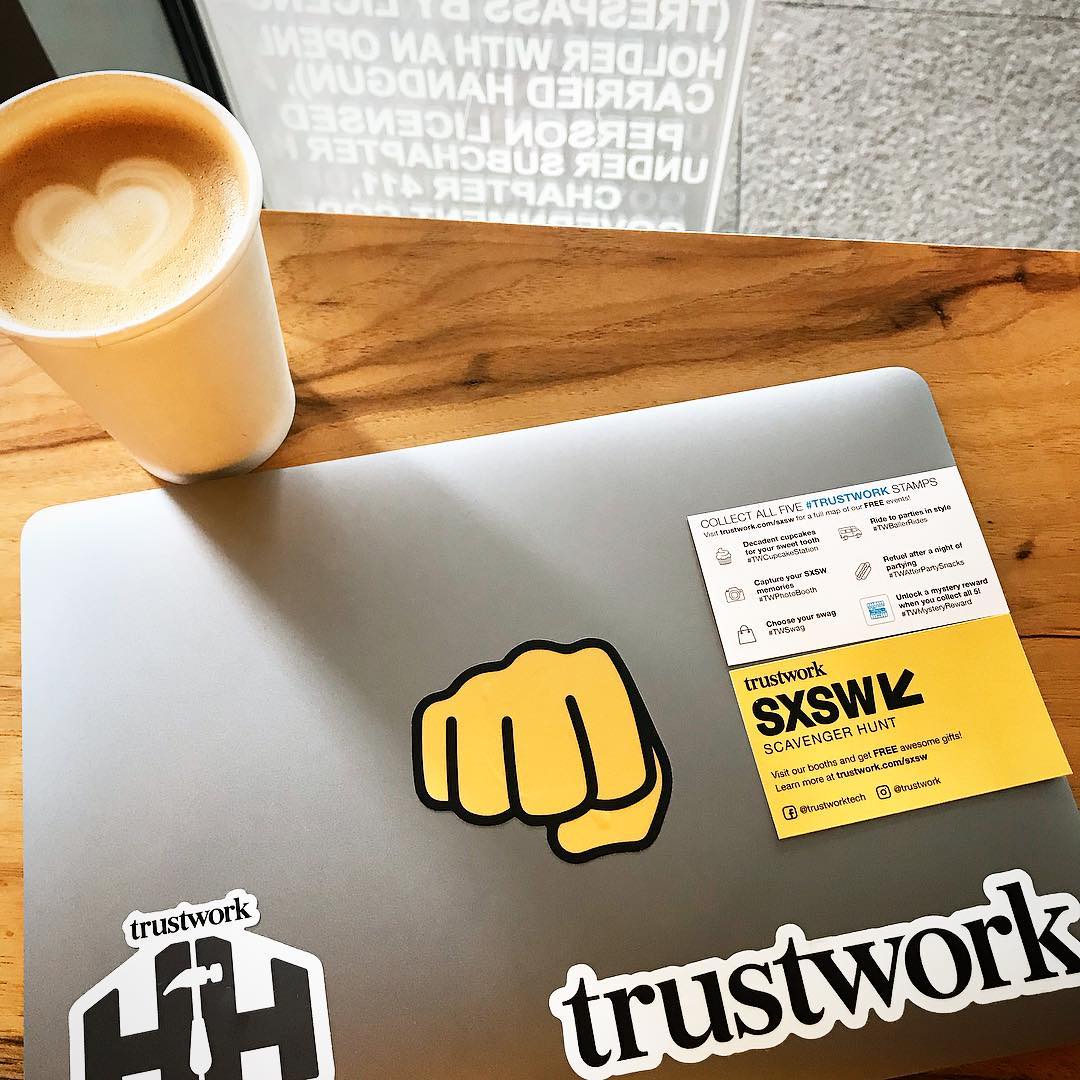

I just got back from taking over SXSW with Trustwork. It was an exhausting eight-day marathon, complete with an air mattress in the office, questionable food, and hundreds of rejections a day. I wouldn’t want to do it again. Despite all that, it was a fantastic experience, and I’m really glad it happened.

For reference — Trustwork is essentially a jobs marketplace, backed by professional profiles for each user. It’s like the marketplace of Craigslist plus the reputation of LinkedIn plus the on-demand aspect of Uber. For the past week, our team of 20 stood on various street corners in downtown Austin giving out a variety of free stuff in exchange for user signups, one at a time. Most days were 10+ hours across a day shift and night shift; at our best we were sustaining over 200 signups an hour.

](https://files.tanagram.app/file/tanagram-data/prod-feifans-blog/sxsw-1.png)

Rejection

At some point on the second day, rejections started feeling normal. When someone said no to a free bag, it stopped feeling like a personal failure; I’d simply move on to the next person walking over. This was due in part to a natural detachment (more on this below), but mainly my track record — I knew that every few minutes, someone would come along who would say Yes and sign up. All those rejections in between were simply part of the process to getting to that Yes.

To be entirely fair: we had a signup goal each day, but we didn’t have anything personal on the line. We weren’t being paid per signup, or per day. We didn’t need to get Yeses so we could afford food or shelter. But none of us wanted to let the team down, and unlike hired/outsourced teams, it was our company.

Beginning with day three, I kept a personal rejection quota in mind — my goal was to get at least 200 rejections (an arbitrarily-chose number). I didn’t really keep track during the day; it was intended more as a way to prime my mind than an actual goal.

At some point I realized that the people passing by were only rejecting what I had to offer. It wasn’t personal; they were saying no to “free shirt?”, not me. This led to a natural detachment made it easy to de-personalize each rejection.

I spent time working each giveaway station, and came to see that the rejection rate varied dramatically based on the item and positioning. Free pizza and cupcakes were easiest. Free photos (akin to a mobile photo booth) were the hardest; we fell flat, and axed the idea halfway through the first day. (Photo booth was later resurrected as the hardest-to-find item on the scavenger hunt, to greater success.)

Finally, sometimes the rejections were downright funny. A sampling:

- To “Free photo?”: “I can take my own ** photo”

- To “Free cupcake?”: “I ain’t eatin’ that shit!”

- To “Do you have a phone [for free pizza]?”: “No man, I lost it last night tripping hard on acid”

Personal Interactions

Sometimes, a Yes turns into a great interaction, in a variety of ways:

- People have interesting stuff on their phones. Typing in “tr”, some brought up Trump results. Others surfaced a search for “trust fund baby”. Adult content, unsurprisingly, made an appearance as well.

- Sometimes we’d ask people to add a profile photo. Many people took selfies on the spot, and posed in a variety of ways. Occasionally, they’d want to take a selfie with us. After one particular photo I took with a guy, he said “dang, you look like a damn model!”

- The first step in our signup asks for a phone number. One guy saw that we were successfully exchanging pizza for numbers, asked us for an empty box, and proceeded to go around trying (unsuccessfully) to get phone numbers until I asked him to do that somewhere else.

- A few days in, a group of guys came by and said “You guys are legends!” They’d gotten the free cupcakes, limo ride, and shirt, and told us that Trustwork made them think of “hustling entrepreneurs”.

- Free pizza and free limo rides offered to a late-night crowd led to some interesting interactions. Details are left to the imagination.

- I found myself matching the volume and mannerisms of the people I talked to. I slipped into more accents than I thought possible, and said “hey man” (which I normally never use) enough times to embarrass a hippie.

Satisfaction

The combination of late-night shifts and activation energy (the willpower needed to prime my mind at the start of each shift) made for an exhausting week. But on balance, the entire experience was deeply satisfying, and I’m very happy to have done it.

Something really interesting happens when you work closely with a group of people and share in the struggle of a difficult task. At some point, quite suddenly, people let down their guard, and you get to know what they’re like at a more human level. This leads to better stories, funnier jokes, and shifts the balance of selective memory (more on this below).

Across hundreds of interactions with strangers, I was fortunate to make a bunch of observations on human behavior and how people used their phones. More on this in Part 2.

Most of those interactions were a net positive — ranging from the satisfaction of closing a Yes, the incredulity when people realized we were giving away free pizza (I was asked “why are you doing this?” several times), and the excitement of our scavenger hunt winners. This further shifts the balance of selective memory and contributes to that feeling of deep satisfaction.

Since each interaction was relatively quick and occurred frequently, it formed a rapid feedback loop allowing me to improve my pitch and selling ability. I settled on three versions of my pitch, tailored to different listeners and varying in complexity, and committed them to muscle memory so I could focus on other interaction details (identifying who was interested, who had the slowest phone in a group, and loading the signup page on my phone to make it easy to set everyone up). Mastering the pitch allowed me to get into a state of flow when interacting with a group of people, and it was exhilarating to perfectly narrate and time the pitch and signup process across a group of three or four people.

Coming into this week, I would not have thought that street-corner sales was something that I could do. I’m happy to have proven myself wrong — to know that it’s something I’m capable of doing, and that I even enjoy it.

](https://files.tanagram.app/file/tanagram-data/prod-feifans-blog/sxsw-4.jpg)

Selective Memory

Selective memory is an extension of the idea that people remember how they felt, but not the details, as well as the peak-end rule. If you know yourself well, you’ll know the types of details that you’ll remember and forget after an experience is over. For example, I know I’ll remember the conversations where everyone can’t stop laughing, the satisfaction of delivering joy to strangers, and discovering cool restaurants in a new city — but I’ll forget the hassle of setting up an air mattress each night.

If you’re deciding whether to do something, selective memory can be used as a framework (possibly in combination with fear-setting) to discount certain aspects of the experience to determine if it will be a net positive.